Why the FCC's net neutrality plan is under fire

James Delahunty

26 Apr 2014 10:02

The FCC has come under fire this past week with the emergence of proposals to allow Internet Service Providers to charge fees for access to 'fast lanes' on their networks.

It was as recent as December 2010 when the FCC put forth its proposals to preserve the free and open Internet by way of regulation that would, undoubtedly, nip any such two-speed system in the bud. U.S. service providers would like to be able to charge bandwidth-hungry services like Netflix to provide them with prioritized access to their network's users, and it seems that until now the FCC has been completely opposed to such access fees.

The FCC's Open Internet Order, dated December 23, 2010, spells out three basic rules which were Transparency, No blocking, and No unreasonable discrimination.

"Fixed broadband providers may not unreasonably discriminate in transmitting lawful network traffic," it reads.

The key word may be "unreasonably", but later on in the same document, the FCC makes clear its disagreement with the main arguments in favor of paid prioritization (e.g. that third party paid prioritization would aid network investment, while regulating against it would hurt investment) and states that, "it is unlikely that pay for priority would satisfy the 'no unreasonable discrimination' standard."

The paper reaches this conclusion after highlighting four main concerns with commercial agreements between broadband providers and third parties (content providers etc.) to directly or indirectly favor some traffic over other traffic passing through the ISP's connection to and from a subscriber:

- Pay for priority is a departure from the current accepted norm and from the history of the Internet. Internet service providers have not typically charged third party content or application providers for access to (whether prioritized or not) the Internet subscribers paying for access to the networks.

- Pay for priority has the potential to stifle innovation and investment in new Internet-based ventures, with such access fees being barriers to newcomers who may end up having to pay to reach a critical mass of potential end users.

- Non-commercial end-users such as bloggers, advocacy groups, educational institutions, libraries and so forth may be harmed by pay for priority becoming a norm.

- Service providers would be incentivized to limit the quality of service provided to non-prioritized traffic, or favor their own services.

So with those four main concerns highlighted by the FCC in recent years, what exactly has changed in the past days that has so many people and organizations up in arms?

New FCC proposals could permit third-party-paid-priority

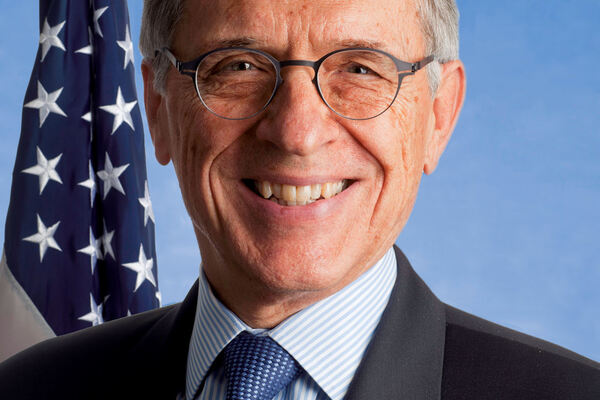

According to reports, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler is circulating proposals for new rules on the issue of network neutrality. The bulk of the Open Internet Order of 2010 (cited above) was rejected by a federal court after the rules were found to exceed the FCC's authority. Most notably, the Telecommunications Act prohibits the FCC from enforcing common carrier obligations on bodies that are not classified as common carriers (like ISPs).

In February, Chairman Wheeler said the regulator is committed to protecting the open Internet and will do so under Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act. However, it may be impossible to adopt realistic net neutrality rules that befit its definition under Section 706. An analysis by Stanford Law Professor Barbara van Schewick shows that with Section 706 and the Verizon v. FCC findings in mind, only rules that leave sufficient room for individualized bargaining and discrimination in terms may be upheld in court.

"Any network neutrality rules adopted under Section 706 by design must offer less protection against discrimination than the Open Internet Rules, or they will pose the same legal problems and will be struck down in court," writes Professor van Schewick.

"Verizon v. FCC explicitly requires the FCC to allow access fees. The Court found that a ban on access fees – even in the somewhat weaker form embodied in the Open Internet Rules – effectively requires Internet service providers to hold themselves out indiscriminately to serve all applications and content providers at a price of zero."

It would appear that the FCC's shift on this issue is down to the telecommunications act, and the interpretation of it in the Verizon v. FCC case, rather than at any time having been convinced by data or evidence that its prior position was the incorrect one.

FCC responds to media reports on new proposals

In response to the media reports and almost uniformly critical reaction from all angles, Chairman Wheeler took to the Official FCC blog to set the record straight. The FCC has not, Wheeler asserts, abandoned its position on the issues in the Open Internet Order, and remains committed to the underlying goals of transparency, no blocking of lawful content, and no unreasonable discrimination among users. The Chairman notes two relevant points:

- The Court of Appeals made it clear that the FCC could stop harmful conduct if it were found to not be "commercially reasonable." Acting within the constraints of the Court's decision, the Notice will propose rules that establish a high bar for what is "commercially reasonable." In addition, the Notice will seek ideas on other approaches to achieve this important goal consistent with the Court's decision. The Notice will also observe that the Commission believes it has the authority under Supreme Court precedent to identify behavior that is flatly illegal.

- It should be noted that even Title II regulation (which many have sought and which remains a clear alternative) only bans "unjust and unreasonable discrimination."

He goes on to state that the draft Open Internet Notice of Proposed Rulemaking upholds the three basic rules enshrined in the 2010 order:

- That all ISPs must transparently disclose to their subscribers and users all relevant information as to the policies that govern their network;

- That no legal content may be blocked; and

- That ISPs may not act in a commercially unreasonable manner to harm the Internet, including favoring the traffic from an affiliated entity.

Response from Net Neutrality advocates

As you would expect, advocates of Network Neutrality principles are on the offensive. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) warns that any rules put in place that leaves the door open for ISPs to charge companies for preferential treatment (e.g. Netflix or Amazon) to reach subscribers on their network faster (videos buffering faster etc.) would be profoundly dangerous for competition, potentially making ISPs gatekeepers to their subscribers.

It also notes the use of the term "commercially reasonable", which is open to interpretation. When the FCC issues a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, the public is invited to comment to the FCC about how the proposal affects the interest of the public, and the FCC is required to respond to public comments by law.

Public Knowledge has also taken issue with the use of the term "commercially reasonable."

"The FCC is inviting ISPs to pick winners and losers online. The very essence of a "commercial reasonableness" standard is discrimination. And the core of net neutrality is non discrimination. This is not net neutrality. This standard allows ISPs to impose a new price of entry for innovation on the Internet. When the Commission used a commercial reasonableness standard for wireless data roaming, it explicitly found that it may be commercially reasonable for a broadband ISP to charge an edge provider higher rates because its service is competitively threatening.

"It is hard to see how the commercial reasonableness standard, which inherently offers less protection than the standard in the previous Open Internet Rules, can serve the same policy goals. Additionally, approaching discrimination on a case-by-case basis creates less certainty than clear rules and disadvantages small businesses and entrepreneurs. The Commission should instead seek to find a way to ensure true net neutrality, including protections against discrimination by ISPs for commercial purposes. The DC Circuit Court opinion made it clear that the only way to achieve net neutrality is to reclassify internet access as a telecommunications service."

- Michael Weinberg, Vice President at Public Knowledge

A Whitehouse.Gov petition also has gathered more than 21,500 signatures as time of writing. It is titled, "Maintain true net neutrality to protect the freedom of information in the United States."

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Verizon v. Federal Communications Commission decision: www.cadc.uscourts.gov (PDF)

Open Internet Order of 2010: hraunfoss.fcc.gov (PDF)

The FCC changed course on Network Neutrality: cyberlaw.stanford.edu (by Prof. Barbara van Schewick)

FCC's New Rules Could Threaten Net Neutrality: www.eff.org

Setting the Record Straight on the FCC's Open Internet Rules: www.fcc.gov (by Chairman Tom Wheeler)

FCC To Allow Commercial Discrimination on the Internet: www.publicknowledge.org